By Benjamin Chan, BS, MD/MPH Candidate, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami and edited by Leila Posaw, MD, MPH, Dept. of Emergency Medicine, Jackson Memorial Hospital

I am a fourth-year medical student with a keen interest in emergency medicine. I understand how hypotensive patients in shock can be a formidable challenge. However, I also believe that point-of-care ultrasound can assist in overcoming this challenge in several ways. One such way is the Rapid Ultrasound for Shock and Hypotension (RUSH)1 exam, which is a comprehensive assessment protocol performed with ultrasound that provides valuable information on why the patient in front of us is in shock. However, while the RUSH exam informs us on the possible causes of hypotension, it does not direct management.

Recently on my ultrasound elective, I read a very interesting article2, which proposes the addition of Velocity-Time Integral (VTI) to the standard RUSH protocol. The goal of resuscitation in shock is to increase stroke volume. The VTI is a surrogate for stroke volume, and can not only be used to predict a patient’s response to fluids (“fluid responsiveness”), but it can also guide resuscitation with the administration of fluids or inotropes.

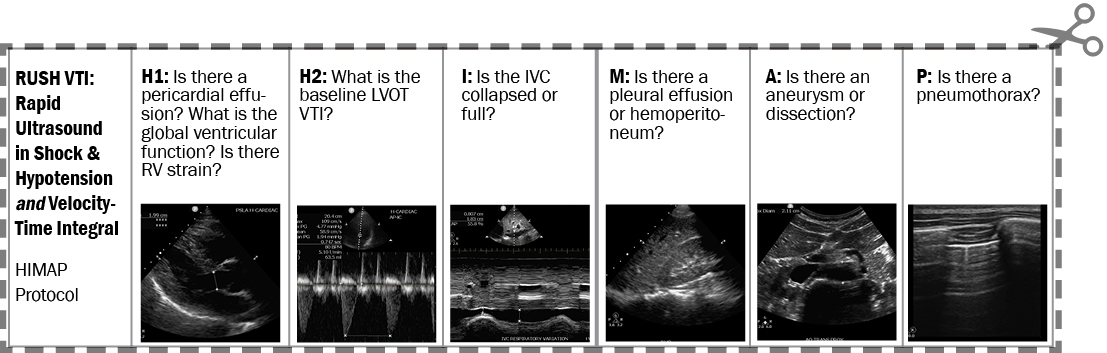

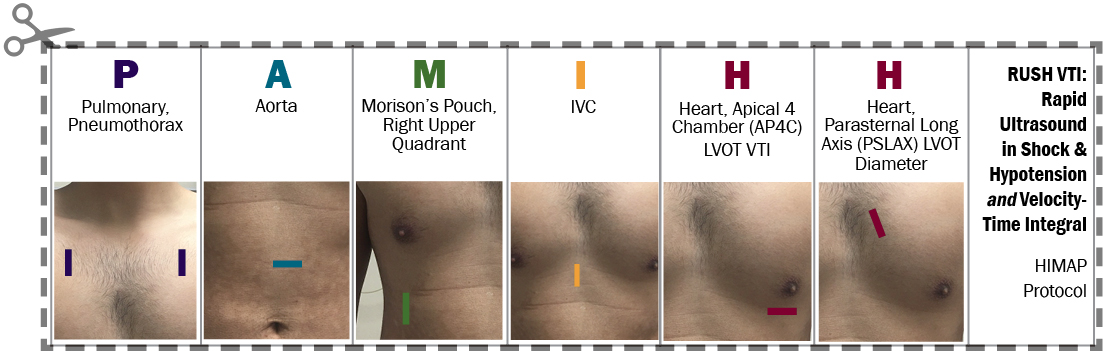

RUSH

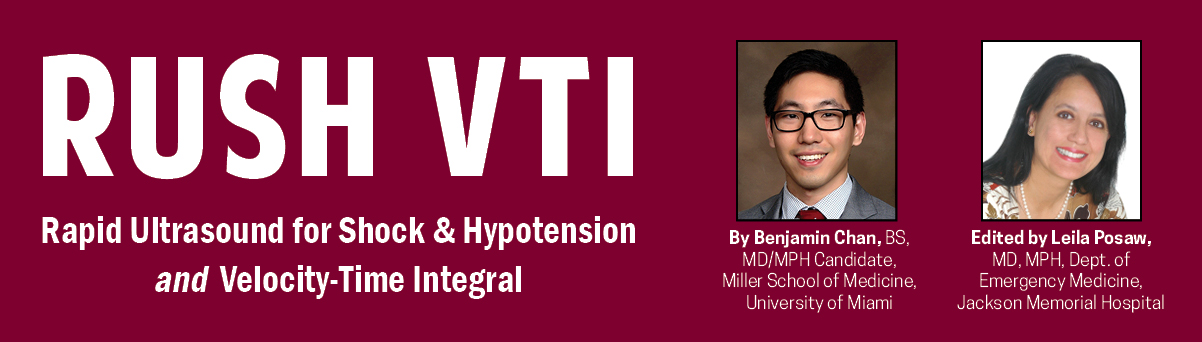

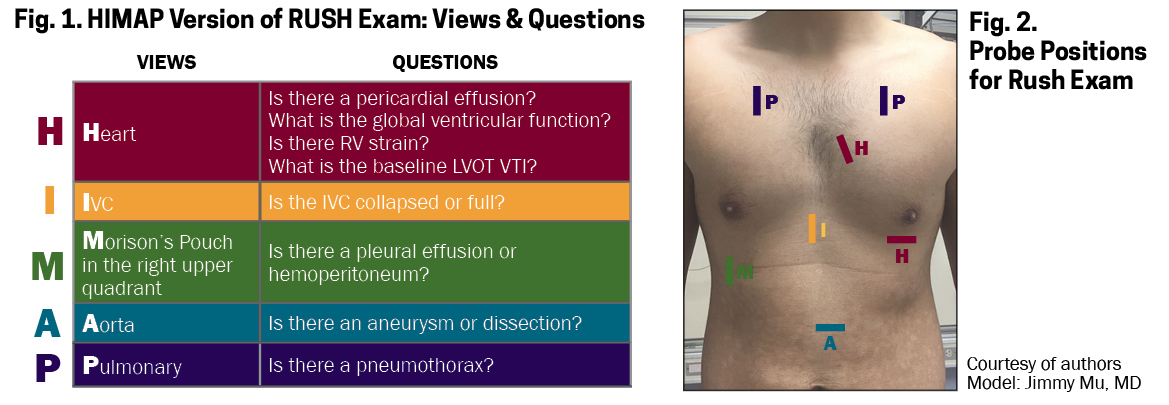

While there are several forms of the RUSH protocol, I find that the HIMAP version (Figs. 1-2) is easy to remember and perform. Technically, it is performed in the B-mode using a curvilinear or phased-array probe.

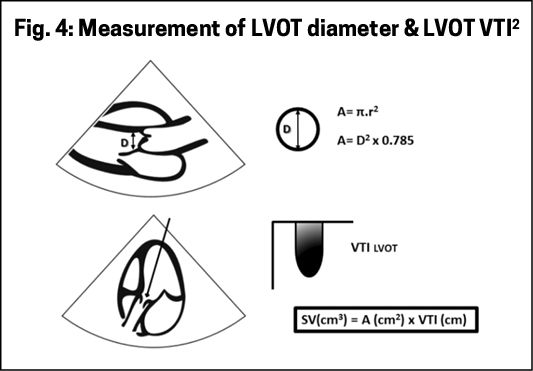

Traditionally, stroke volume is calculated with this equation:

[LVOT VTI x (LVOT diameter)^2 x 0.785]

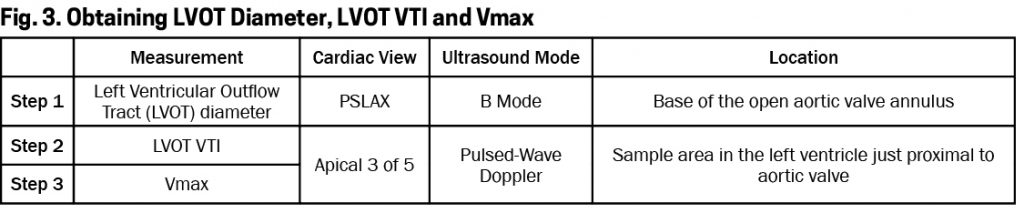

Technically, it is performed with a phased-array probe in the B-mode and Doppler mode as depicted in Fig. 4. It is important to place the pulsed-wave marker directly in line with the LVOT blood flow and to place the pulsed-wave sampling gate in the correct location, otherwise your LVOT VTI measurement might not be accurate.

Measuring LVOT diameter in emergent situations can be technically difficult and errors are magnified due to the squaring of the diameter in the equation. An easier and more accurate alternative is to only measure the LVOT VTI (step 2) and omit the LVOT diameter (step 1), which remains constant in all calculations. Similarly, it would be even simpler to use the Vmax (step 3) rather than the LVOT VTI (step 2) because it obviates the difficulty of tracing around the VTI curve using the ultrasound machine cursor.

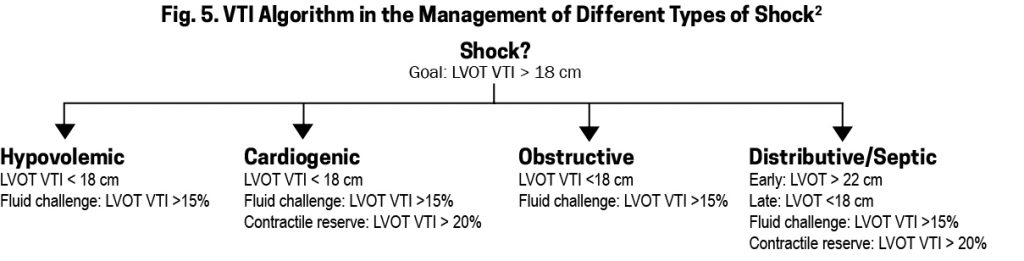

A normal LVOT VTI is between 18 and 22 cm for heart rates between 55 and 95 beats per minute.

LVOT VTI is limited as a surrogate for stroke volume in conditions of dynamic LVOT obstruction and moderate to severe aortic regurgitation. If the VTI cannot be obtained on the LVOT because of these or other technical difficulties, then other potential sites for measuring VTI include the right ventricular outflow tract, the mitral valve and the descending aorta.

Management

Simply, stroke volume (SV) can be increased with fluids or with inotropes. Fluid responsiveness is defined by an increase in SV of greater than 15% after a fluid bolus. Contractile reserve is defined as an increase in SV of greater than 20% after administration of inotropes. The concept of measuring stroke volume pre- and post-intervention (fluid bolus, inotropes or other interventions) has been shown to be more important than static measurements.

We know that fewer than half of hypotensive patients will increase their stroke volume as a response to fluids. Which patients are these? We can easily discern this by measuring the LVOT VTI (or the Vmax) prior to and after a fluid challenge (small fluid bolus or passive leg raising). An increase of more than 15% would indicate fluid responsiveness. A simplified VTI algorithm in the management of different types of shock is depicted in Fig. 5.

All emergency departments manage critical hypotensive patients. Instead of the usual mantra of “let’s give 2L of fluid” to every hypotensive patient, I look forward to managing my patients with ultrasound. Seeing with ultrasound will be my superpower.

References

1. Weingart, S. (2008). https://emcrit.org/rush-exam/original-rush-article/ Accessed: 8/31/2018.

2. Blanco, P., Aguiar, F. M. and Blaivas, M. (2015), Rapid Ultrasound in Shock (RUSH) Velocity-Time Integral. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 34: 1691-1700.

RUSH VTI.To.Go.